(Shout out to my summer section of Introduction to Philosophy who graciously evaluated my argument and previewed this essay. Thanks!)

From the convention stage down to my Facebook feed, I feel like the public conversation has grown thick with rhetoric. Don’t get me wrong. Between the most recent repetitions of racial injustice, all too common acts of gun violence and the current dysphoric election cycle, I think there are plenty of legitimate reasons to be worked up, to be critical and to be angry. Persuasive speech is appropriate and inevitable. However, when rhetoric gets ratcheted up, we risk miscommunicating our position in favor of enflaming passion.

Among the oratorical misdeeds common to our current conversation, I want to focus specifically on confusion between moral condemnation and ethical censure. What I’m not suggesting is some feeble retreat to “making nice.” As a feminist, I’m very aware (and terrifically weary) of the way politeness has been used to silence dissent. Rather, I believe at the current moment we have necessary, hard things to say to one another and just as importantly, we need especially to be clear if we hope the conversation will be productive. The difference between moral and ethical is a nuanced one. While both attempt to distinguish between “good” and “bad,” those conclusions are reached in significantly different ways. I think making a distinction between them can help us more accurately hear one another.

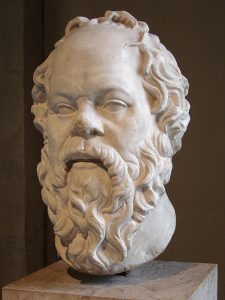

When I teach Introduction to Ethics, one of the first texts I have students read is Plato’s Euthyphro. First of all, Euthyphro introduces students to the basics of philosophical argument. Philosophical argument, in turn, forms the logical foundation of ethics. In ethics, right and wrong is judged by reason. Secondly, Euthyphro draws out how morality, in contrast to ethics, approaches questions of conduct. In the text, the philosopher Socrates questions the title character, Euthyphro, about his motives for prosecuting his father for the murder of a family slave.* This was a strange act in Greek society given both the cultural reverence of the father figure and the widespread existence of slavery. When Socrates presses him, Euthyphro answers that he is prosecuting his father for the sake of “piety” or “holiness.” Throughout the rest of the play, Euthyphro attempts to define “piety” to the satisfaction of Socrates (SPOILER ALERT: he doesn’t do a great job).

Why does Socrates drill down on the word “holy?” Apart from rigorous interrogation being the hallmark of the

Socratic method, it’s because holiness indicates something beyond being merely correct or logically acceptable. By using “holy,” Euthyphro seems confident that what he is about to do is not only right, but also better than other courses of behavior. Euthyphro sees himself as occupying a vantage point from which he can better judge the situation. In Euthyphro’s case, this position is a result of his religious worldview; what he is doing is approved by or for the sake of the gods.

But morality should not be understood as being confined solely to religion. Broadly speaking, the signature of morality is that it appeals to authority and tradition first, reason second. Sometimes, religion is that authority, but the ethnic or political communities may play that role of tradition as well. To say that morality appeals to reason second is not to say that morality can’t be reasonable. It’s more like saying: because of my upbringing, I believe that 3 + 2 is the preferable way to get to 5. 3 + 2 is a perfectly reasonable way of adding to 5, but preferring it over 4 +1 is just a matter of what I was taught to believe.

I’d also like to avoid the misunderstanding that morality is necessarily arrogant. The distinctive of morality isn’t “better than you,” it’s “what’s best for us.” They reveal who we think we are as much as what we think to be good or evil. Because it is grounded in authority and tradition, morality comes from within a particular community, a specific perspective. It’s important to note that typically, my identity is not in question during the course of an issues based conversation. Rather, I speak out of my community of origin. Therefore, moral assessments add a dimension of identity that can’t be ignored.

So in public conversations, which are conversations that span across communities and identities, it’s really helpful to understand whether an objection is being made on moral or ethical grounds; in other words, whether it is more part of someone’s traditionally held beliefs or whether it is more about what makes sense. This helps me to distinguish what’s on the table in the conversation. When we ignore the difference we lose opportunities to agree with one another or we potentially argue over the wrong point.

Let me give a personal example: I am a vegetarian who doesn’t eat meat for ethical reasons. Although there are plenty of vegetarians who abstain from meat for moral reasons, I’ve decided to land my diet lower on the food chain because I think it makes sense as a more fair way to share in the world’s food supply. I don’t think eating meat is necessarily evil. Making that distinction in conversation has allowed me to have discussions with meat eaters about issues we might agree on like conservation and resource distribution. I’ve even learned some things about sustainable meat-eating practices (although I remain untempted).

As another example, I grew up in a faith community that taught homosexuality was wrong. This is a moral judgment drawn from traditional teachings on portions of sacred texts. Growing up, I accepted this position along with many other moral positions shared by my faith community. As I became an adult however, I met members of the LGBTQ community (very patient and gracious members) who made a compelling ethical case for equal treatment under civil law. Even before I began to question my moral assumptions about queer sexuality, I could agree that it made sense that civil rights should be extended to all citizens. This initial agreement opened the doors for me to begin exploring my religion for other voices and teachings on the issue. Eventually, I decided both that the judgement of homosexuality as morally wrong should not be accepted uncritically within my faith tradition and also that I no longer wanted to associate with a faith tradition that held those views.

It is equally helpful to observe cases in which the distinction cannot be made, instances when morality and ethics strongly align. I would argue racial injustice (police profiling and brutality, higher rates of arrest, sentencing inequities) is both unethical and immoral. It does not make sense to apply the law differently on the basis of race; also, doing so attacks the belief that all persons are equally due basic human dignity.

Distinguishing the moral from the ethical does not provide us with a no fail recipe for civil conversation. Far from being an easy fix, it may initially make matters seem more complex. However, if we practice speaking more precisely about the origins of our concerns, we have a better chance of focusing on solutions that we might all agree on.