Spoilers for DIE HARD, obviously.

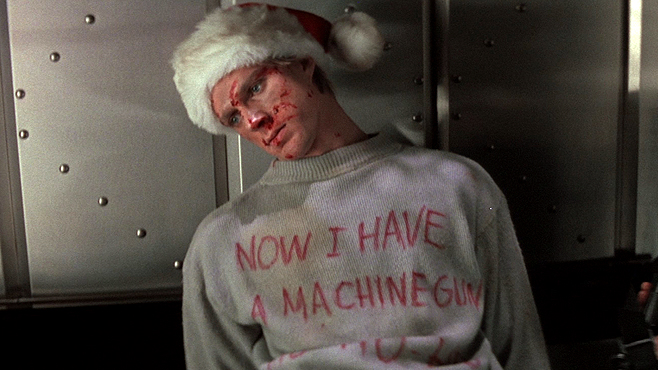

He staggers into the light, machine gun held more by its strap than his two hands. Shirtless, covered in blood – his and others, and exhausted, he is a specter of death.

He staggers into the light, machine gun held more by its strap than his two hands. Shirtless, covered in blood – his and others, and exhausted, he is a specter of death.

Holly Gennaro, held tight in the grip of self-proclaimed “exceptional thief” Hans Grueber (whose free hand points a gun at Holly’s temple) – Holly gasps, “Jesus!”

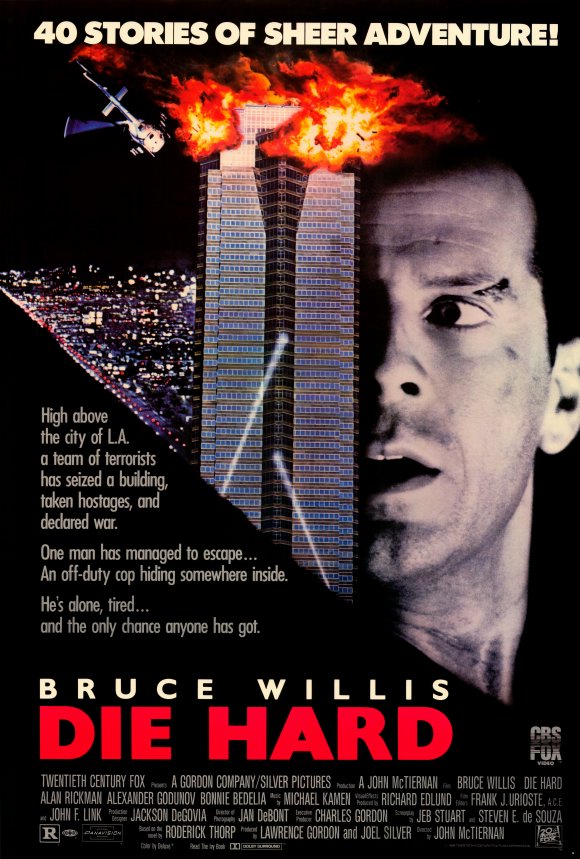

Holly is not taking our Lord’s name in vain. Rather, in this moment, she recognizes that her husband’s ordeal in the Nakatomi tower has transformed him into a savior – hopefully her savior. John McClane’s journey is the journey of Christmas, the journey of the Incarnation, and it’s why DIE HARD is not only one of the greatest action films of all time, it’s also (at least in my mind) the quintessential Christmas tale.

Christmas is the story of the birth of Israel’s promised Messiah, but the story takes an unexpected turn in that Messiah is no mere human – he turns out to be the very creator God, who has left the throne of Heaven to become human. Theologians call this the kenosis – the divine self-emptying. We also call it the Incarnation – a Latin word that literally means “enfleshment”.

The infinite God becomes finite. The spiritual becomes physical. The limitless becomes limited. The supreme power of the universe becomes a helpless infant.

Human flesh is inherently weak. We are mortal. Our bodies break down. It’s years of our life before we can even begin to defend ourselves. God’s kenosis, the Incarnation is an essential statement about who God is: God rules through weakness. God wins by losing. This is why the Cross was inevitable for God – because God lives by dying. It’s an upside down reality.

Enter John McClane. Before DIE HARD, action films were about tough guys – terminators, super soldiers, spies and so on. What set DIE HARD apart – and changed the face of action cinema forever, was the “everyman-ness” of John McClane. John isn’t a superhero. He doesn’t have a bunch of special skills. He’s just an average guy driven to do the right thing, to stand up to impossible odds, by love for his estranged wife.

John’s journey is one of incarnation – he leaves the safety and comfort of New York city for the strange world of Los Angeles – much is made in the first act of how strange and uncomfortable John finds Los Angeles. He leaves the streets, where he is comfortably blue collar, to join Holly’s white-collar corporate Christmas party. Like Jesus, John – compelled by love for his estranged bride – leaves his comfort to enter her world.

And this, of course, is when everything goes horribly wrong. Evil takes Holly and her world hostage in the form of a thief who’s come to steal, kill and destroy. John finds himself stripped to a tank-top and pants, barefoot and alone against a small army of terrorists.

John’s ordeal emphasizes his humanity because at every turn, he confronts the limits of his humanity.

He faces his enemies alone. The power structures work actively to subvert him, both because of bureaucratic incompetence and prideful sabotage. His own flesh increasingly gives out on him as he takes more and more punishment. Finally, John rescues Holly by surrendering to Hans. Hands in the air (nearly cruciform), he laughs in the face of his enemy’s taunts – his surrender has been a ruse, and John, because he perseveres, saves his bride.

Jesus similarly effected atonement between God and humanity. According to the book of Hebrews, it was Jesus’ very humanity, his faithfulness through the limitations of his humanity that made him worthy to rescue us:

Although he was a Son, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and having been made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him. — Hebrews 5:8-9

Another way to understand what Jesus accomplished is called Christus Victor or “Christ the Victor”. This model of atonement imagines humanity to be held captive by the forces of evil. Jesus defeats the powers by dying – his supreme act of self-surrender, of apparent defeat, is actually the means through which he overcomes the powers and frees his bride from their clutches.

[God] disarmed the rulers and authorities and made a public example of them, triumphing over them in it. — Colossians 2:15

Both models of atonement are grounded in Jesus’ self-emptying, in the reality of his humanity. Christians call Jesus’ incarnation the good news. It is God’s self-emptying that reveals most fully God’s nature. God’s surprising plan to win by losing reveals the upside-down nature of God’s kingdom. And this is exactly what the Christmas story is all about: God come not as a conquering king but as a defenseless baby, born not in a palace but in a stable. Jesus is the everyman whose very everyman-ness enables him to rescue his bride and inaugurate the new creation.

Why is DIE HARD a Christmas movie? Because Holly Gennaro is right – when John McClane staggers into the light, arms up in surrender, she recognizes him for the Christ-figure he is.