This review was originally featured at RELEVANT Magazine.

Click HERE to read the full review now!

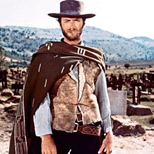

The Western has always been an opportunity for Americans to explore our mythic identity. At least since Davey Crockett was born on a mountain top in Tennessee, the Cowboy has always been larger than life, capable of just a bit more than the rest of us. The Cowboy is who we want to be, who we could be.

The Western has always been an opportunity for Americans to explore our mythic identity. At least since Davey Crockett was born on a mountain top in Tennessee, the Cowboy has always been larger than life, capable of just a bit more than the rest of us. The Cowboy is who we want to be, who we could be.

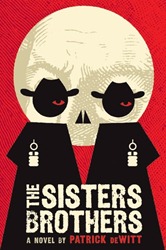

The Sisters Brothers invites us to stare into its funhouse mirror, if we are brave enough.

The Sisters Brothers introduces us to the notorious assassins Charlie and Eli Sisters. The Sisters Brothers work for the Commodore, a shadowy, powerful figure living in Oregon City in the mid-1800s. He dispatches Charlie and Eli – who’ve just barely survived their most recent assignment – to obtain a certain formula from one Herman Kermitt Warm – who was last seen in San Francisco – and then kill him.

Eli narrates the Brothers’ quest, their slow-but-steady journey towards the insanity of San Francisco at the height of the Gold Rush. Eli comes across as a kind, thoughtful and simple fellow. He’s self-conscious about his weight, terribly lonely and quietly desperate for a different life. Eli connects easily with everyone he meets and feels a particular sympathy for the powerless and disenfranchised. (Even the plight of his poor horse, Tub, causes Eli tremendous misery.)

Charlie couldn’t be more different. Loud, brutish and short-tempered, Charlie drinks too much, abuses the whores he sleeps with and idolizes powerful, cruel men like the Commodore. Charlie revels in the spoils of his occupation. He offers contempt and abuse to those he considers beneath him (including Eli), and flattery to those more powerful than he – until he can supplant them.

Charlie couldn’t be more different. Loud, brutish and short-tempered, Charlie drinks too much, abuses the whores he sleeps with and idolizes powerful, cruel men like the Commodore. Charlie revels in the spoils of his occupation. He offers contempt and abuse to those he considers beneath him (including Eli), and flattery to those more powerful than he – until he can supplant them.

As the title suggests, the Brothers are night and day, yin and yang. They highlight the deep-seated contradictions in our own cultural character.

The Brothers’ journey to San Francisco showcases their differences, but also establishes their deadly character. Whether he’s manipulated into killing by Charlie or not, Eli is deadly. Between the two of them, the Brothers can out-trick, out-think and out-shoot anyone who crosses their path. Eli narrates the violence he enacts so dispassionately it’s easy to miss how thoroughly gruesome is the path they carve to the Golden Coast.

In fact, the level of violence the Brothers wage is matched only by their utter disregard for the appalling nature of their kills. Not unlike how easily we disregard our nation’s own violent history and present by turning the page or changing a channel.

In fact, the level of violence the Brothers wage is matched only by their utter disregard for the appalling nature of their kills. Not unlike how easily we disregard our nation’s own violent history and present by turning the page or changing a channel.

Eli most clearly embodies this contradiction. He’s so genuinely likeable that his violence is especially shocking. But Eli’s kindness might make it possible for us to be more honest about our own history. Admitting to a legacy of violence doesn’t leave us villains.

The world of The Sisters Brothers – like our own – is too messy for blacks and whites. Eli inhabits the grey, just like we do.

The Brothers reach San Francisco to learn they should’ve been asking more questions. They discover the Commodore’s true reasons for wanting Warm dead and face a quandary, though even here they differ. Suffice to say it involves getting very rich very quickly. Eli faces a true moral dilemma – apparently Warm isn’t actually a bad guy – while Charlie sees his opportunity finally to supplant the Commodore. The body count – both human and animal – continues to rise as the Brothers plod ever closer to the surprising climax and equally unforeseen but tenderer epilogue.

As interesting as its view of violence is the novel’s attitude towards wealth. The delirium of Gold-Rush-era San Francisco is foolish enough to be farcical, unless you’ve ever been to a store (any store, it doesn’t matter) on Black Friday. And none of us seems to be immune to the power of the almighty (dollar), just as the normally steadfast Charlie and Eli are caught up in Warm’s seemingly foolproof get-rich-quick scheme. And it’s not that the gruesome outcome of Warm’s plans are a metaphor for the recent economic woes. It’s that the pursuit of wealth always ends thusly.

As interesting as its view of violence is the novel’s attitude towards wealth. The delirium of Gold-Rush-era San Francisco is foolish enough to be farcical, unless you’ve ever been to a store (any store, it doesn’t matter) on Black Friday. And none of us seems to be immune to the power of the almighty (dollar), just as the normally steadfast Charlie and Eli are caught up in Warm’s seemingly foolproof get-rich-quick scheme. And it’s not that the gruesome outcome of Warm’s plans are a metaphor for the recent economic woes. It’s that the pursuit of wealth always ends thusly.

As any great Western does, The Sisters Brothers mythologizes our contemporary struggles for meaning. Eschewing both violence and pursuit of wealth, the novel points us toward the beauty found in a life lived with those we love. Or, you know, maybe it’s just a story.