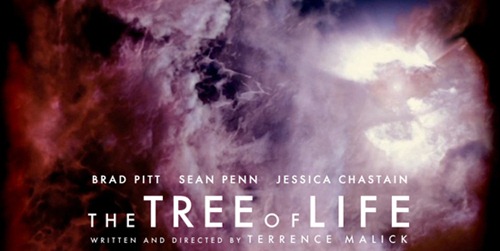

Before we get started, let’s note that Tree of Life is too big a film to fit inside a review. Writer/director Terrence Malick has crafted a sprawling epic that is at once as intimate as a small-town American family and as large as the whole history of the universe. There’s a story, but it’s too small for the film – the themes spill over the bounds of the narrative, so watching the film feels closer to walking through an art gallery than reading a book.

Before we get started, let’s note that Tree of Life is too big a film to fit inside a review. Writer/director Terrence Malick has crafted a sprawling epic that is at once as intimate as a small-town American family and as large as the whole history of the universe. There’s a story, but it’s too small for the film – the themes spill over the bounds of the narrative, so watching the film feels closer to walking through an art gallery than reading a book.

Grounded firmly in the Biblical story, Tree of Life explores the ancient question: Why do bad things happen?

The film opens with a quote from the book of Job:

Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?… When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

— Job 38:4, 7

Here, God is responding to Job, who has spent the first 37 chapters of the book trying to figure out why he suffers, even though he serves God. When God finally shows up, rather than offer Job any concrete, helpful answers, God responds by taking Job on a whirlwind tour of creation history.

Here, God is responding to Job, who has spent the first 37 chapters of the book trying to figure out why he suffers, even though he serves God. When God finally shows up, rather than offer Job any concrete, helpful answers, God responds by taking Job on a whirlwind tour of creation history.

So too in Tree of Life. The film opens on Mrs. O’Brien, who receives a telegram letting her know that her second son, R.L. has died (in Vietnam?). We then meet the oldest O’Brien son, Jack: a business man estranged from his parents (Sean Penn).

Jack’s life is consumed by asking why R. L. died, and by extension why Life doesn’t happen the way it should.

Malick answers Jack’s question the same way God answered Job’s: he takes Jack the viewers back to the creation of the world, and we see scene after beautiful, awe-inspiring scene of Life moving forward. We finally land in the Garden of Eden – 1950s Small Town America. Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien (Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain) as Adam and Eve live the paradise of the American Dream, have three boys and faithfully attend Church.

Malick answers Jack’s question the same way God answered Job’s: he takes Jack the viewers back to the creation of the world, and we see scene after beautiful, awe-inspiring scene of Life moving forward. We finally land in the Garden of Eden – 1950s Small Town America. Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien (Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain) as Adam and Eve live the paradise of the American Dream, have three boys and faithfully attend Church.

All the components of our original mythology are there – Adam working the land, Cain and Abel, the Fall from innocence. Expulsion from the Garden. But Malick never lets Tree of Life become a crude allegory. He handles themes without forcing them into the scenes, leaving us always grasping at the meaning, always feeling that the story watching is bigger than the story we’re seeing.

All the components of our original mythology are there – Adam working the land, Cain and Abel, the Fall from innocence. Expulsion from the Garden. But Malick never lets Tree of Life become a crude allegory. He handles themes without forcing them into the scenes, leaving us always grasping at the meaning, always feeling that the story watching is bigger than the story we’re seeing.

We resonate with Mr. O’Brien’s agony at the failure of his legalism. We understand Jack’s rage at his mother’s unwillingness (or inability?) to rescue him from his father’s strong hand. We’ve all experienced loss. These themes make Tree of Life a quintessentially human film.

Our life journeys are always both unique and common. Individual and human.

Jack’s journey is the heart of the film. It’s his grief, his questioning. We hear his mother’s voice early on:

There are two ways through life: they way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you’ll follow.

For Jack, these two Ways are embodied in his mother:

For Jack, these two Ways are embodied in his mother:

Grace doesn’t try to please itself. It accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked. Accepts insults and injuries.

And his father:

Nature only wants to please itself, get others to please it too. Likes to lord it over them, to have its own way.

Throughout the film we watch Jack struggle between these two poles, these two modes of living, of grasping the world. And we are Jack, children of the first Father and Mother, living with the consequences of their choices. We are Cain, our basically unfair lives unfolding around us. And we are Job, questioning the basic Goodness of the universe. We cry out with Jack:

Father. Mother. Always you wrestle inside me. Always you will.

In the end, Jack’s answer is as ambiguous as was Job’s.

In the end, Jack’s answer is as ambiguous as was Job’s.

But unlike Job, Jack glimpses not just creation history but creation future. Jack sees a Resurrection with his family and all those who comprised his life.

Jack emerges from his vision to a cityscape under a bright blue sky. And his answer is our answer: bad things happen, but the God who is too big for our stories is bringing all things to Resurrection. As Jack’s mom promises:

No one who loves the way of Grace ever comes to a bad end.