100 years ago, America was off to war in what was the biggest event in human history to that time–World War I. Women had been trying to gain the right to vote for decades. By 1917, the woman suffrage movement had split.

Alice Paul led the establishment of the National Woman’s Party (NWP) after being rejected by Carrie Chapman Catt and the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Catt thought Paul and her colleagues were too radical, too militant, even though Catt appreciated how often her rivals got the Susan B. Anthony Amendment in the newspapers.

Women were second class citizens, not allowed to vote federally or in most states. Yet the leaders elected by men were able to control their lives. So women had no say when their sons, husbands, and brothers were sent off to The Great War in Europe.

Leaders like Paul, Lucy Burns, Doris Stevens, Dora Lewis, Mabel Vernon, and others weren’t worried about appearing polite to President Wilson and others who refused to enfranchise women.The ladies of the NWP protested in many different ways and at many different places, like when they undercover attended a speech by President Wilson and leaped from the front row to unfurl a banner, which they held in front of him until security intervened.

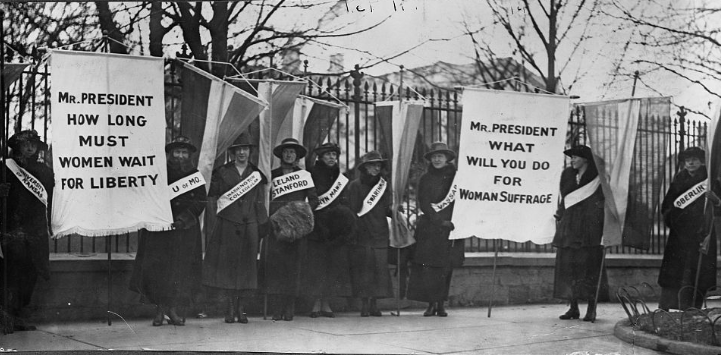

For months in 1917, the Silent Sentinels stood outside the White House with signs demanding change. Rain or shine, they held vigil and let their banners do the talking. They never said a word to leering and jeering onlookers.

And then the United States officially entered World War I. American troops set off for Europe, and 100,000 died within a year.

A lot of good people did what they could to support the war effort. Some purchased war bonds to help finance military needs. Many folks, young and old, planted vegetables in Victory Gardens, because self-sufficiency meant more available resources for the boys overseas. The NAWSA even stopped petitioning Congress to pass a national amendment and instead organized volunteers who knitted socks for soldiers. President Wilson continued to make speeches about the value of liberty and freedom, and the importance of making the world “safe for democracy.”

Alice Paul and the NWP continued protesting.

Critics couldn’t believe they would stoop so low, crying about inequality while men were fighting for their freedom to picket. How dare they attack their national leadership, calling the president “Kaiser Wilson” even. When a few men harassed them and ripped their banner to shreds, they said nothing. But Carrie Chapman Catt had something to say of the NWP’s silent protest:

“We consider it unwise, unpatriotic, and most unprofitable to the cause of suffrage.”

Then the D.C. chief of police called to inform Paul that protests would no longer be allowed in town, silent or otherwise. He warned them to stop or face consequences. The next day, police lined up in rows outside NWP headquarters, daring them to try something.

Scores of suffragists came and went, some hiding new banners under their coats. They split up for diversion. Some walked towards the White House, some to the Capitol, and some to Lafayette Park. They whipped out the banners featuring the president’s own words, things he had said when discussing war. The messages were piercing in their hypocrisy.

But now they had crossed the line. They had used their high profile positions to point out the inequality faced by millions of Americans, and they had done it during a time when “real” patriotism was most important.

The majority was full of sneering critics. How dare they demand true equality in America while their countrymen were over in Europe helping to fix all those other countries that threatened democracy? Protest if you feel it’s really such a big deal and all, but why do you have to do it at a time when we should be rallying around the flag? That’s disrespectful, they said.

And so the suffragists were arrested more than ever. Heavier fines were levied. Their prison sentences stretched from days to months. Free speech should only go so far, it seemed.

“We are at war, and you should not bother the president,” said the judge at one sentencing.

The women were denied basic necessities, even having to beg for toilet paper. They weren’t even given the same food and privileges as convicted murderers. In and out of prison they went.

They continued protesting. Whoever was out of jail would take up new banners and picket still. The gangs of angry critics turned into mobs. Hundreds of voices condemning the women as unpatriotic grew into thousands who accused them of treason. At one point, a mob surrounded the NWP headquarters. The women locked the doors. Sailors climbed onto their balcony and ripped down the American flag hung by the suffragists. Apparently, the angry patriots in the street were the only ones worthy of Old Glory. At last a gun shot was fired through one of the upstairs windows. Local police remained disinterested in the safety of the women but eventually came by to disperse the crowds.

The women activists endured all that and refused to stop until the system was fundamentally changed to live up to the words of the Constitution that had established the system in the first place. They were hated, starved, attacked, and more. But eventually more and more people stopped attacking the public picketing and began listening to the principles behind their protests.

The Nineteenth Amendment was finally passed by 1920, and American women earned the right to vote.

~*~*~

Like what you just read? Check out AMERICAN GHOSTS, a weekly newsletter about the history of what haunts us, how present issues were shaped by the past. You can sign up here and check out a previous example on Protesting the Anthem.