Given the glut of awards ceremonies this time of year, we shouldn’t be overly surprised by the overabundance of what my wife insightfully called “Oscar-porn” movies released in December and (to those of us who don’t live in New York or Los Angeles) January. This year, three films were released at roughly the same time, all of which were vying for the “feel-good” votes. All three are adaptations – two of them “based on a true story”. But only one of them was actually a good film.

Philomena capitalizes on the emotive weight of its source material to tell a complex and profound story. Saving Mr. Banks and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, on the other hand, take story-telling shortcuts and end up manufacture their sentimentality.

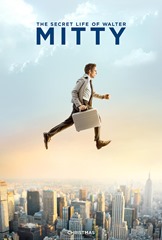

By far the worst offender, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty is the latest film adaptation of the eponymous short story first published in 1939. In the original story, Mitty is a mild-mannered sap, ordered about by his assertive wife. Clearly unhappy with his life, but equally unwilling to enact any change, Mitty escapes into heroic daydreams at a moment’s notice.

In the new film adaptation – directed by and starring Ben Stiller, Mitty has no wife. He’s still cowardly, but in this case, he’s never started a life. Unlike the story, Mitty does decide to act on his adventurous impulses. And that’s the film’s failing.

Mitty gets no character development. In the first scene of the film, he’s scared to send a wink on eHarmony. A handful of scenes later, he’s flying to Greenland, leaping onto helicopters mid-takeoff, plunging into arctic, shark-infested waters and sneaking illegally into Afghanistan. Which is all cool, and visually stunning, and well-acted. But wholly unbelievable.

And be rich!

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty is being hailed (apparently by a lot of people) as “the Forrest Gump of this generation”. Those people either don’t think much of this generation or Forrest Gump.

We like Stiller’s Walter Mitty, and his chemistry with a subdued-but-still-awesome Kristin Wiig. And we all identify with Mitty’s desire to be more adventurous than he is. We all recognize the gap between the life we imagined as kids and the lives we’re actually living. But Walter Mitty’s advice to fill this gap is, apparently, “just quit your job and buy a plane ticket around the world.

I’m pretty sure the official hash tag of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty is #FirstWorldProblems

— JR. Forasteros (@jrforasteros) January 1, 2014

In other words, maybe this whole “live the life you’ve always wanted” thing is a privileged problem. And if that were the film’s subversive point, kudos. But it wasn’t.

No Emotional Depth

Saving Mr. Banks wasn’t much better. Based on the true story of how Walt Disney convinced Mary Poppins author P. L. Travers to adapt her beloved character for the big screen, Saving Mr. Banks oozes sentimentality. But here, too, the film’s disingenuous presentation undercuts the weight of the emotion.

Though Travers is presented realistically (and expertly by Emma Thompson), Hanks’ Disney is – ironically, perhaps – a caricature of a real person. His boundless optimism and relentless insistence on bringing Mary Poppins to film make Travers’ reluctance seem wholly irrational.

Saving Mr. Banks was clearly trying to present Disney as a man who loved all children – even damaged children who grow up into unhappy adults. And it obviously worked for some people. Saving Mr. Banks whitewashes Disney the man, presenting him as an idealized father-figure with no flaws or frustrations. So instead of a deeply human film about reconciling our feelings about imperfect parents, Disney the mega-corporation movie studio delivers us saccharine, forgettable hero-worship.

You’ll cry at the end of Saving Mr. Banks not because the film earned your tears, but because they pushed every “sad” button and flipped every “sap” lever at their heavy-handed disposal.

Where Saving Mr. Banks seems to resonate with anyone, it’s because the film reminds them how much they loved Mary Poppins. If what makes your film work is how much it reminds viewers of how much they loved a different film, your film isn’t very good (I’m looking at you, All Saints Day).

Now consider Philomena. Also based on a true story. Also a deeply emotional. But the story of Philomena Lee is presented much more honestly, so it becomes a beautiful meditation on motherhood, faith and cynicism. Philomena (played to heartbreaking perfection by Judi Dench) has a simple, plain faith that clashes loudly with Sixsmith’s cruel, jaded cynicism.

Philomena’s earnest kindness gradually wins Sixsmith over – we get to watch it in the film. Their budding friendship transforms him into a crusader on her behalf against the Church that wronged her. We accompany Philomena on her own journey of forgiving herself. So when she refuses to allow Sixsmith to fight for her, choosing instead to respond to her victimizers with love and forgiveness that arises not from ignorance or simplicity but courage and faith, we are overwhelmed, inspired and shamed with him.

None of the characters in Philomena is idealized, which makes our emotional connection to their journeys more authentic and rewarding.

None of the characters in Philomena is idealized, which makes our emotional connection to their journeys more authentic and rewarding.

The issue in these films is not that sentimentality is inherently bad or stupid. In fact, any good film connects with us on a deeply emotional level. But precisely because emotion is so strong, it’s easy to fake. Put in a sad story about a parent, or kill off a minor character or show some audience wish-fulfillment, and the film will feel pretty amazing.

But when the emotional journey isn’t authentic, the film feels hollow. That’s why, in the end The Secret Life of Walter Mitty and Saving Mr. Banks underwhelm. It’s reflecting in the awards nominations, the RottenTomato ratings. Watch all three and you marvel at how much more profoundly Philomena speaks to you.