Click here to listen to the StoryMen discuss NOAH in depth.

The controversy over Darren Aronofsky’s new film NOAH has been… shocking… to say the least. As I suggested in my last post – 5 Things You Need to Know-a Before Seeing NOAH, a lot of the disappointment has been due to wrong expectations. Most Evangelicals wanted a strict remake of Genesis 6-9, while Aronofsky set out to create an artistic midrash of the Flood story.

The controversy over Darren Aronofsky’s new film NOAH has been… shocking… to say the least. As I suggested in my last post – 5 Things You Need to Know-a Before Seeing NOAH, a lot of the disappointment has been due to wrong expectations. Most Evangelicals wanted a strict remake of Genesis 6-9, while Aronofsky set out to create an artistic midrash of the Flood story.

But many Evangelicals who’ve seen the film are crying that NOAH is unbiblical, calling for boycotts and in general expressing outrage at how far Aronofsky strayed from the Biblical text. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Though it plays fast and loose with some details, NOAH is a profoundly biblical film, giving life to deep themes present in Genesis 1-11.

1. NOAH respects the cosmology of Genesis 1-11.

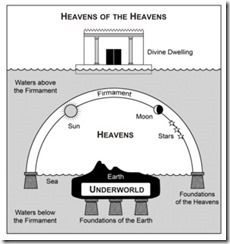

Ancient peoples didn’t see the Earth the same way we do. Not only do we have the creation accounts in the Bible to show us that, but we have maps various ancient cultures created that show us how differently they imagined the world. We see the Earth as the third planet in our solar system, comprised of earth and minerals. Earth is a mostly-solid sphere inside which is molten earth, the surface of which is 70% covered in water, and all of this suspended in space.

The Ancient Hebrews who wrote Genesis 1-11 saw the Earth as a flat disc of Earth that served as the base for a dome of sky, in which hung the sun, moon and stars. Outside the disc – both above the sky and below the land – was nothing but a hostile chaotic uber-sea called the Deep.

NOAH preserves this strange (to us) cosmology, at least from the characters’ perspectives. Though we do get a few shots from outer space of the flood, and a Big-Bang-to-Missing-Link visualization of the creation story (neither of which would’ve made any sense to Noah or his contemporaries), the characters themselves do make mention of “the fountains of the deep”, and when the actual flood begins in earnest, those same fountains explode through the Earth.

Certainly the flood portrayed in NOAH was not a natural disaster. Aronofsky portrayed it as the apocalyptic, world-ending event Genesis intended it to be.

2. NOAH illustrates the tension between agrarian life and human progress.

Beginning with Adam creation in Genesis 2, humanity is tasked to till and keep the ground, to work the soil. After the Fall, Adam’s work is the same; it only becomes harder. Many commentators read the tension between Cain (a farmer) and Abel (a herdsman) in part as an illustration of the human shift to an agrarian economy (from primarily one that relies on animals). Later in Genesis 4, Cain’s line continues this innovation, creating everything from cities to music to metallurgy.

NOAH presents this tension in its two leads – Noah himself and Tuba-Cain. Noah, the last son of Seth, lives off the land. He tells his sons that they take only what they need. Tubal-Cain, on the other hand, leads humanity in the wanton consumption of the Earth’s resources.

This tension is prominent in Genesis – it runs from the Garden of Eden through Noah to the Tower of Babel in chapter 11. To see it represented so well in NOAH was a pleasant surprise.

3. NOAH presents wickedness as violence against creation.

I understand why people are claiming NOAH has a pro-Environmental message (I still can’t figure out why that’s such a bad thing). What makes me laugh cry is that many of these same persons complain that such a pro-Earth message is unbiblical. The first two commands God gives to humanity in Genesis 1-2 are to “fill the Earth and govern it” and “till and keep the Garden [of Eden].” Though the human wickedness running rampant in Genesis 6 isn’t explicitly described as an improper stewardship of God’s good world, it’s certainly not a leap to tell the story in that way, particularly if we pay attention to the technological progress of Cain’s line.

NOAH illustrates two different ways to understand God’s command to Adam and Eve. The first, embodied in Noah, is that of the steward: our job is to care for the planet, to work for its flourishing. We’re here to nurture it.

The other is embodied in Tubal-Cain (the inventor of metallurgy, according to Genesis 4:22). Tubal-Cain announces multiple times that he’s the master of creation, that his status as an image-bearer of the Creator gives license do do as he pleases. In other words, he’s a tyrant. He believes the world exists for him, to be consumed as he pleases.

A disregard for God’s creation is sinful. It’s idolatrous. And it’s most definitely a biblical theme.

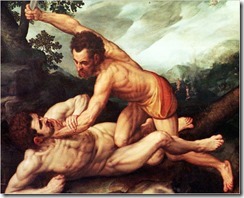

4. NOAH illustrates the escalating violence of Genesis 1-11.

Only a few generations after Cain’s first murder, violence has spiraled out of control. By way of protecting Cain, God vowed that anyone who hurt him would receive back seven times as much as they did to him. Just a few generations later, Cain’s descendant Lamech (Tubal-Cain’s father), upped the ante, promising that anyone who harms him will be repaid seventy-seven times.

Only a few generations after Cain’s first murder, violence has spiraled out of control. By way of protecting Cain, God vowed that anyone who hurt him would receive back seven times as much as they did to him. Just a few generations later, Cain’s descendant Lamech (Tubal-Cain’s father), upped the ante, promising that anyone who harms him will be repaid seventy-seven times.

NOAH repeatedly returns to the image of Cain striking down Abel to symbolize the violence humans were willing to do to each other in Noah’s day. Cast in silhouette, that first murder became the shadow of every act of anger, of vengeance, of pride, in the film. Most striking, toward the end of the film, the shadow remained on the screen, and Cain morphed into every perpetrator of violence in human history, becoming an ancient spearman, a bow-wielder, a Revolutionary soldier, a modern-day, machine gun wielding trooper. Abel becomes the victims of violence, including a Native American among others.

NOAH ties our violence against each other to the fundamental brokenness at the core of the human heart.

5. NOAH refuses to ignore the ugly parts of the Flood story.

One of two scenes that will haunt me for a long time is inside the ark, just after the Flood has finally hit. Noah and his family are gathered around a simple meal, and outside, they can hear the screams of all those who’re drowning in the floodwaters.

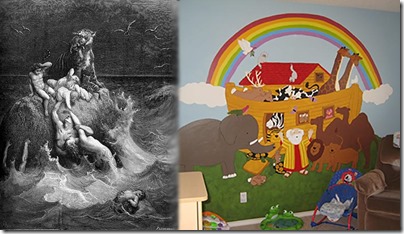

This grisly aspect of the Flood story is one we deliberately suppress in our rush to turn Noah into a flannel-graph and his ark into nursery decorations. But the Bible presents the Flood as an apocalypse, an End of the Cosmos scenario enacted by God as a response to humanity’s refusal to live in God’s world on God’s terms.

That shouldn’t be something we overlook as we tell the Flood story – it’s the whole point of the narrative.

NOAH presents the stakes of the Flood story clearly and compellingly. It’s nothing less than an Apocalypse.

6. NOAH admits that God’s re-creation wasn’t completed.

The other scene that will continue to haunt me for a long time is that final moment on the Ark, when Noah stands, knife in hand, over Ila and her twin girls. Noah has convinced himself that God’s plan includes the final destruction of humankind, the source of Sin and Death, so these new girls – who represent new life, a new beginning for humanity – must be killed.

But as he later tells Ila,

I stood over those girls, intending to kill them.

But there was only love in my heart. – Noah

What this choice meant for Noah’s (fantastic) character journey is worth its own post. But suffice to say, the Bible does present Genesis 8 as a re-creation. The parallels between Genesis 1 and Genesis 8 have long been noted by scholars.

What this choice meant for Noah’s (fantastic) character journey is worth its own post. But suffice to say, the Bible does present Genesis 8 as a re-creation. The parallels between Genesis 1 and Genesis 8 have long been noted by scholars.

What makes it all the more curious is what Noah observes in the film: the only part of creation not remade is the one part of creation that broke everything – humankind.

The celebratory air of Genesis 8 is quickly undone by Noah’s drunken stupor in chapter 9. By the Tower of Babel in chapter 11. It’s clear that this new creation isn’t any better off than the old one, that the sons of Seth are also the sons of Adam, and have inherited his sinfulness.

NOAH takes seriously the sinful nature of every human, our continuing need for rescue and God’s eternal offer of mercy even in the face of judgment.

You broke my heart.

So there you have it. For all the details that NOAH changed, it kept some deep, powerful and so very biblical themes. I left the film staggered by the obvious amount of respect Aronofsky has for the story of Noah, and for the amount of blood, sweat and tears he packed into this marvelous blockbuster.

And in the interest of full disclosure: I liked plenty of the non-Biblical stuff too. I loved the rock-monster-Nephilim-Watchers and their story arcs. I loved how the world still had a little bit of magic left in it, only 10 generations removed from Eden. And Ham’s journey, as well as Tubal-Cain were incredibly compelling.