Your universe was never meant to be. — Malekith

THOR: The Dark World expands Marvel’s cinematic universe, refining the cosmic scope we first glimpsed in Thor and revisited in The Avengers. We see more of the 9 Realms, meet the Collector and discover that the tesseract is one of the Infinity Stones.

We also learn that the universe is not eternal – it had a beginning. That’s not exactly a news flash, but Odin the All-Father also tells us that before our universe existed, something else did. Or didn’t. Sort of.

That “something” is darkness, a malevolent evil embodied in the Dark Elves and their Aether, another of the Infinity Stones. Except unlike its five counterparts, the Aether manifests not as stone, but as a liquid.

And that would all be nothing more than a little fun, fantastic world-building were it not for the presentation: THOR: The Dark World presents our universe as an aberration, a disruption to the natural, chaotic state of the (non)universe. Life, the universe and everything – existence itself – exists because long ago the gods of Asgard defeated the forces of evil (the Dark Elves) in combat, thus ensuring the universe could exist.

Surprisingly, THOR 2‘s combat worldview hews more closely to what we find in the Bible than the scientific worldview we have today.

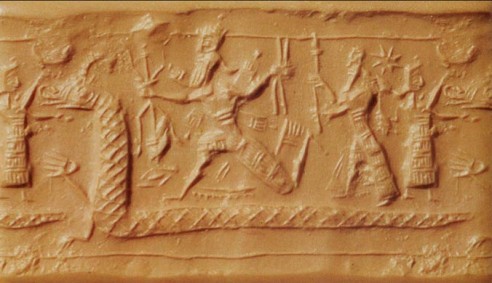

We find a world created through combat in the creation stories of many ancient cultures, including those of the Ancient Near East. The peoples surrounding Ancient Israel – including Babylon and Canaan – saw the world as a carefully constructed, constantly sustained and protected space.

Their creation stories follow a similar pattern: the oldest recognizable deities are embodiments of water – Tiamat in Babylon, Yam in Canaan. Yam is often pictured as a multi-headed serpent (which’ll matter in a minute). And their champion god – Marduk and Ba’al, respectively – slays the water god, then pides its body to create the universe out of the space between.

So if you were an ancient Babylonian (or Canaanite, or one of the other cultures that held a combat worldview), you saw your life as a gift. Your god defeated the powers of chaos and darkness (which are embodied in the seas) and created a space in which life can exist. Life (your life, your family and people’s lives, all life) continues only because your god constantly, continually holds back the waters of darkness and chaos. This is why worship was such a central part of your life: by participating in your god’s worship, you participated in maintaining a space for your life – and all Life – to flourish.

While the Bible doesn’t exactly tell a creation story of combat mythology, it does still bear the marks of the combat cultures around it. A more grammatically accurate (but less familiar to our ears) translation of Genesis 1:1-2 reads,

When God began to create the heavens and the earth, the earth was formless and empty, and darkness was over the surface of the Deep.

When God began to create, the earth was “formless and empty”. It’s a phrase that in Hebrew refers to that chaotic evil, that lack of form and function that characterized Tiamat and Yam.

There’s not nothing there at the beginning. There’s darkness. And water. Just like in Thor 2.

Then, on Day 2 of creation, God separates the waters above from the waters below, creating a space between them called the firmament. This firmament is where God will put land, the space in which life will flourish.

Day two of the Genesis creation week echoes the combat myths of the surrounding cultures. It’s the separation of the waters, the building of a space for life, stripped of all combat.

Other biblical passages bear explicit witness to the kind of Combat Creation we’d expect in an Ancient Near Eastern culture. Several texts speak of God’s relationship to Leviathan (most famously, Job 41:1-34) and Rahab, two mythical sea monsters that appear in Canaanite mythologies as embodiments of the chaotic seas, parallels to Yam.

Most explicit is Psalm 89, which presents God as the pine warrior triumphing over the seas:

Oh YHWH, God of the armies, who is as mighty as you, oh YHWH?

Your faithfulness surrounds you.

You rule the raging of the seas. When its waves rise, you still them.

You crushed Rahab like a carcass; you scattered your enemies with a mighty arm. — Psalm 89:8-10

Likewise, Psalm 74 presents God as the champion over Leviathan:

God my king is from of old, working salvation in the earth.

You divided the sea by your might, you crushed the heads of dragons in the waters. You crushed the heads of Leviathan, you gave him as food for the creatures of the wilderness. — Psalm 74:12-14

These texts both demonstrate Israel’s Combat Creation worldview: Rahab and Leviathan are both equated with Yam, imagined as multi-headed dragons God destroyed and separated in the act of creation.

In the worldview of the Bible, life is a fragile thing that must be cultivated and protected. And only God is able to defeat the dark forces that threaten his fragile creation.

So too in Thor: The Dark World. Thor is the divine warrior, waging battle for the very existence of the universe against forces that would extinguish the fragile flame of life.

Life Finds a Way.

That life is fragile, that we would depend upon a god not just to flourish but to survive runs counter to the contemporary scientific mythology.

Our existence is allegedly overshadowed by our universe’s total heat death, as prophesied by the Second Law of Thermodynamics. And yet embedded in this (relatively) new mythology is that famous dictum made famous by Ian Malcolm, the chaotician of Jurassic Park: Life finds a way.

The underlying assumption verbalized by Dr. Malcolm is that life possesses some ineffable quality within itself to endure, to thrive, to flourish no matter what conditions the cold, dark universe brings to bear on it. The scientific myth directly contradicts the combat myth: life needs no god to defeat the darkness. Life is enough in and of itself.

That we need a god – any g0d – to flourish is a rather counter-cultural message.

There’s even the smallest bit of Jesus imagery in there, when Thor defeats Malekith and the Aether by plunging headfirst into battle. When all is said and done, Odin tells him:

All the Nine Realms saw you sacrifice yourself for them. You’ve earned your throne. — “Odin”

The divine warrior who demonstrates by his self-sacrifice his worthiness to rule the universe. It’s not quite St. Paul. But it’s not bad for a comic book movie.