Fair warning: Lots of spoilers for The Witch ahead.

And if you like spoilers, you might as well listen to the Don’t Split Up! podcast review of the film!

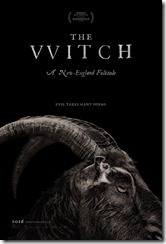

Last year’s Sundance horror darling The Witch finally hit theaters this weekend. Anticipation had only been heightened following an endorsement from the Church of Satan, who declared it “a Satanic experience” that “will signal a call-to-arms for a Satanic uprising against the tyrannical vestiges of bigoted superstition, and will harken a new era of liberation and unfettered inquiry.”

Last year’s Sundance horror darling The Witch finally hit theaters this weekend. Anticipation had only been heightened following an endorsement from the Church of Satan, who declared it “a Satanic experience” that “will signal a call-to-arms for a Satanic uprising against the tyrannical vestiges of bigoted superstition, and will harken a new era of liberation and unfettered inquiry.”

That the statement is hyperbole is beside the point. What’s more interesting is why Satanist are endorsing the film. The critique of religion in The Witch that resonates with the Satanic Church ought to resonate with Christians as well.

We ought to champion the message of this film along with the Satanic Church, and perhaps push the critique even further.

The Witch is set in 1630 New-England and follows a family exiled from their Puritan plantation because they’re too religious. Read that sentence again and let the implications set in. The film is well-acted and the dialogue is pitch-perfect so the strict Puritan Calvinism is on full display.

After a witch steals the infant Samuel (and makes him into a paste in which she bathes), young Caleb asks his father if Samuel is in Hell. William replies that only God knows who is chosen and who is not, so to offer Caleb an answer would be empty falsehood.

As the film builds, William and Katherine wonder why God is tormenting them and have no answers – do they have secret sins? (They do.) Has God simply cursed them for inscrutable reasons? They have no way of knowing; they can only try harder to be holy.

As their plight grows more desperate, the parents determine there must be a witch among them, and they cast their suspicions on Tomasin, whose budding sexuality is suddenly a threat to the careful order of their little clearing.

As Vox observes, this is exactly what the Satanic Church loves about the film. They believe that “theocratic patriarchy has created a society that’s untenable to everybody who’s not already in power.” Jex Blackmore, a spokesperson for the Satanic Church, reads The Witch as “a film about what happens when you realize the Christian patriarchy has some serious problems… There is an interest in controlling a female figure and in dictating to her what her role is in a society that benefits males.”

As Vox observes, this is exactly what the Satanic Church loves about the film. They believe that “theocratic patriarchy has created a society that’s untenable to everybody who’s not already in power.” Jex Blackmore, a spokesperson for the Satanic Church, reads The Witch as “a film about what happens when you realize the Christian patriarchy has some serious problems… There is an interest in controlling a female figure and in dictating to her what her role is in a society that benefits males.”

This is all true, particularly of several historic forms of Christianity that treat women as second-class humans.

The Satanic Church is right to resist these forms of Christianity. But so should anyone who follows Jesus.

A religion that systematically denies women bear the full image of God is not good. A religion that insists women are not equally gifted, equally called and does not equally equip women to lead is oppressive and unjust. A religion that insists women are objects of desire, whose bodies are dangerous to men and must therefore be strictly monitored and controlled is evil.

Moreover, the Calvinism evidenced in The Witch is morally abhorrent. A father cannot comfort his son (or his wife) in the face of the death of an infant because his God is capricious and inscrutable. He can offer no assurances and fears even to offer comfort to his children lest they become morally lax – though what that would look like on the frontier is a mystery. (At least the father is theologically consistent, doubting even his own salvation. New Calvinists of today lack the theological humility found among the Puritans.) Every religious conversation in the film repeatedly affirms how wicked and depraved the family is, despite the fact that no one but the father has committed anything resembling a sin.

Moreover, the Calvinism evidenced in The Witch is morally abhorrent. A father cannot comfort his son (or his wife) in the face of the death of an infant because his God is capricious and inscrutable. He can offer no assurances and fears even to offer comfort to his children lest they become morally lax – though what that would look like on the frontier is a mystery. (At least the father is theologically consistent, doubting even his own salvation. New Calvinists of today lack the theological humility found among the Puritans.) Every religious conversation in the film repeatedly affirms how wicked and depraved the family is, despite the fact that no one but the father has committed anything resembling a sin.

This Patriarchal Calvinism leaves Tomasin with no recourse but the evil of witchcraft, which should serve as a warning to the religious among us.

After the witches of the woods drive the family to terror and death, Tomasin is left alone and without options. She cannot return to the Plantation as she will surely be tried and executed as a witch. So she is left to implore Black Philip for aid, and she becomes a witch.

After the witches of the woods drive the family to terror and death, Tomasin is left alone and without options. She cannot return to the Plantation as she will surely be tried and executed as a witch. So she is left to implore Black Philip for aid, and she becomes a witch.

But this is no romantic ending. These are not good witches. They have murdered at least two children and terrorized an innocent family. Tomasin’s choice is not between an evil religion and something beautiful (if pagan). It’s between being killed or becoming a killer herself.

The Wesleyan theological tradition offers a preferable alternative to either awful extreme. We affirm God not as capricious but all-loving, salvation not as an unknowable mystery but sacred gift. Women are not threats to masculine centers of power but equals, co-laborers in the garden of God’s good world.

The Wesleyan theological tradition offers a preferable alternative to either awful extreme. We affirm God not as capricious but all-loving, salvation not as an unknowable mystery but sacred gift. Women are not threats to masculine centers of power but equals, co-laborers in the garden of God’s good world.

As long as Christians insist on marginalizing women, we give the Witch her power. We rob the Church of half her gifts. We make a mockery out of Jesus’ good news. The Church of Satan is right – that sort of religion should be resisted at all costs. The Witch offers us a chilling morality tale that displays the horrifying consequences of such religion.