What makes a good villain? The term is oxymoronic – villains are bad, of course. Villains scare us, but why? Why are some bad guys scary and others not so much? Fiction is an easy window into this question – the “best” fictional villains can reflect real-life bad guys and help us to understand how we respond to real monsters.

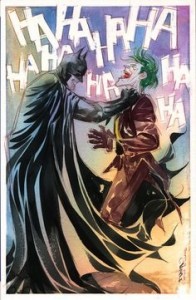

When it comes to comic book villains, the Joker tops nearly every list (and the lists that don’t put him there go to great lengths to explain his absence). And in the real world, it’s hard to find a more universally feared and despised person than Adolf Hitler.

The Joker and Hitler are true cultural monsters. They embody our deepest fear – that anyone can become a monster.

We always fear what we don’t understand, and most villains we can file into one of two categories: “Had His Reasons” or “Just Plain Evil”. When someone shoots up a school, we are glued to the newsmedia and their shrill, incessant pseudo-analysis because we want to file them, to be able to say, “Oh he was abused,” or “His brain just didn’t work right,” or “He was bullied,” or “He played video games and watched a movie once.”

Nearly every other comic book villain fits. Take Magneto, Zod or Loki, to mine recent film history. Magneto was interred in a concentration camp for being Jewish. Loki has an inferiority complex and Zod is a race-supremacist.

They’re “Had His Reasons”. We understand Magneto’s conviction – based on his experience of the Holocaust – that humanity will try to kill mutants for being different. We feel bad for Loki even as we disapprove of waging war on Manhattan. We understand Zod even as we root against him (he’s the last of his race, humans are like ants compared to him, blah blah blah).

They’re unquestionably bad guys, but we understand their reasons, so they’re less frightening.

But the Joker doesn’t have reasons – or rather, he doesn’t have any reasons that make any sense.

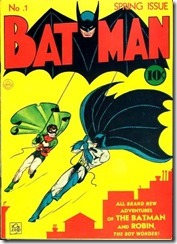

The Joker started out as all the Bat-villains did: a concept with a shtick:

- The Riddler told riddles.

- Catwoman was a cat burglar who dressed in a cat suit.

- The Joker looked like a jester and used items purchased from a joke shop – a lapel flower that squirted acid, a joy-buzzer that delivered a too-strong shock.

As comics evolved, the Batman’s rogues gallery weathered the changes better than others. Somehow, nearly every corny old villain received an update that made the gags make sense in a modern context:

- The Riddler had an abusive father who was obsessed with truth-telling.

- Two-Face was already maybe a bit unhinged and obsessed with the duality of right and wrong.

- Catwoman… is a cat burglar who wears a cat suit (because it’s sexy, I guess?).

But again and again, the Joker has defied an origin story. Alan Moore’s landmark The Killing Joke establishes he fell into a vat of acid and was transformed into the Joker – he was the victim of “One Bad Day” just like the Batman. But despite the hallowed place Moore’s Joker occupies in Bat-history, his Joker-origin has been jettisoned. In Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo’s recent Zero Year, they retell Moore’s Joker-origin. Some fans were outraged that Snyder had confirmed Moore’s Joker-origin as canon. Snyder was quick to point out they had done no such thing, leaving the Joker’s origin ambiguous. Snyder’s clever writing echoes The Dark Knight’s Joker (played by Heath Ledger), who gives no fewer than 3 different accounts of “how I got these scars”.

Why is Joker the greatest comic villain? Because he denies us empathy.

Now consider the other kind of villains, those we’ll soon see in upcoming films. Ultron is a robot who takes his programming too literally (and ultimately becomes a Terminator-style warning of the limits of human progress). Thanos and Darkseid are both essentially wholly unsympathetic despots.

These are “Just Plain Evil.” Ultron’s not human, so we have no problem reveling in his inevitable defeat. Thanos, Darkseid, Doomsday and others are so evil they’re wholly unsympathetic. Rooting against them doesn’t cause us any internal conflict at all. We like our villains pure and simple.

Consider this question: Stalin killed way more people than Hitler. So why isn’t he the great monster of the 20th century?

I read a provocative analysis once (and I forget where, so if you’re the author, please let me know and I’ll credit you!) that pointed to the numerous pictures we have of Hitler playing with his dog (who’s name was… wait for it… Blondie), or with his niece. The pictures are clearly part of Josef Goebbles’ propaganda machine, but they terrify us in a way similarly-staged pictures of Stalin don’t.

The difference is that we believe the pictures of Hitler.

By all accounts, Hitler could be a staggeringly likeable person. He was charismatic, engaging and fun. Hitler was apparently the sort of guy you’d have a backyard BBQ with, and after he left, turn to your spouse and say, “What a nice guy. We really need to hang out with him more!”

Stalin wasn’t like that. Stalin was cold and stiff. He was dour, angry, generally not any fun at all. In other words, he was exactly the sort of person you wouldn’t want to have over, let alone running a country with a sizeable military.

Here’s the difference: Stalin took power, but Hitler was elected.

Stalin is a tyrant, a despot. He’s a monster we understand because he comes in, seizes control and kills all who oppose him. He’s “Just Plain Evil”, and his personal demeanor matches. He’s not warm, friendly or fun – how could he be? He’s evil. Of course those pictures of him having fun are staged. Stalin can’t have fun, he can’t be likable because he’s evil. No one in their right mind would’ve voted for Stalin, so he took all the power he had, and we’re not surprised that once he seized control he executed a reign of terror.

This is why, in Guardians of the Galaxy, Thanos sits on a big chair hovering over a barren asteroid in the middle of space. It’s why Darkseid’s homeworld is a fiery wasteland called Apokalips. Of course they don’t live anywhere we’d want to visit – they’re evil.

But Hitler refuses to fit into those categories. He was (apparently) fun. He was (apparently) kind, at least to some people. He played with kids and dogs and (apparently) genuinely enjoyed himself. He was such a charismatic guy that he won multiple national elections. As much as we desperately want Hitler to be Just Plain Evil, he wasn’t. And that makes him the most monstrous of all.

This kind of monster truly scares us because we can’t recognize him.

The Joker scares us because we can’t explain him. Loki, Magneto, Zod, these villains we understand. And because we understand them, we are confident we are nothing like them. We have learned healthier (or at least more socially acceptable) ways to face our inadequacies than leading an alien army on Manhattan. Our concern not to repeat the Holocaust drive us to work for justice rather than become the race-supremacists we hate. And we’re committed to the proposition that all people are created equal.

So we like villains we can empathize with because we can be sure we’re not becoming them. But the Joker refuses our empathy. He denies us the chance to understand him, and that’s terrifying. If we can’t discern the road to the Joker, how can we be sure we’re not walking it?

Why is Hitler history’s greatest monster? Because he defies recognition.

Thanos is obviously a tyrant. So is Darkesid. So are Red Skull and Stalin. But Hitler looks like the guy next door. He’s the archetype of monsters like BTK and Jim Jones – people who are at once wholly likeable and completely monstrous. So charismatic that even wise, discerning, intelligent persons fall under their sway and offer their support. So credible they convince us to become monsters ourselves as we follow them.

We like villains who look like monsters because we can spot them from a mile off and wage war on them. But Hitler refuses our careful investigation. He denies us the easy identification of obvious evil, and that’s terrifying. If we can’t spot the monster, how can we be sure he’s not, in fact, next door? How do we know what’s in those hotdogs he brought to the block party?

The scariest monsters are those we can’t readily identify.

The scariest monsters are those we can’t readily identify.

What frightens us most about these unidentifiable, unpredictable villains is that they might be us. When villains are empathetic or dehumanized, we can pretend we don’t suffer from the same temptations, short-comings and failures they do.

Hitler wasn’t born a monster. Neither was the Joker, even if we don’t ever learn his origin story. We would do well to let the disquiet they create in us to seep into how we view the other villains in our lives – those we’ve reduced to monsters and those we understand even as we condemn. Comic books are one thing, but in our world, we need to be reminded that they are not so different from us. That the path that led them to their villainy might be the same road we’re walking right now.

Caution, compassion, empathy, patience, these can help us to avoid becoming the villains ourselves. They might even pave the way to rescue of the villains themselves.