If you haven’t heard of Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy or know that the first of the film adaptations opened this weekend, you’re either living under a rock or possibly just in one of the outlying districts.

If you haven’t heard of Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy or know that the first of the film adaptations opened this weekend, you’re either living under a rock or possibly just in one of the outlying districts.

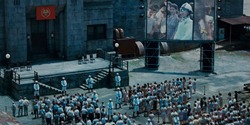

Ostensibly, the novels and film chronicle a dystopian future in which children from the remains of North America must fight to the death as penance for rebellion. But there’s so much more going on:

The Hunger Games is a deeper critique of our contemporary American lifestyle and a call for change… before it’s too late.

Katniss is from District 12, one of the most outlying – and poorest of the Districts. Since she’s the protagonist, we naturally identify with her. We feel her pain as she ekes out a meager existence in 12.

Katniss is from District 12, one of the most outlying – and poorest of the Districts. Since she’s the protagonist, we naturally identify with her. We feel her pain as she ekes out a meager existence in 12.

We share her awe when she arrives in the Capitol. We marvel at the technology, the ease of life, the luxuries so mundane here that are unimagined back in 12. We also scoff at the outlandish fashions of the Capitol, at the wasteful, ostentatious ways the citizens modify their bodies.

We rage at the Capitol for how they exploit children to keep the much-poorer outlying districts in a form of future-slavery, while all the citizens of the Capitol live seemingly unaware off the sweat of their labors.

The problem is we have a lot more in common with the Capitol than we do with Katniss.

The world of The Hunger Games is a thinly-veiled picture of our daily reality. The Capitol is America, living in fantastic luxury relative to the rest of the world. We are surrounded by gadgets we take for granted while our distant neighbors in the Global South often go without even running water. We waste tons of food and spend billions on advertising, mostly aimed to convince us to purchase yet more unnecessary products that we’ll probably end up throwing away.

The world of The Hunger Games is a thinly-veiled picture of our daily reality. The Capitol is America, living in fantastic luxury relative to the rest of the world. We are surrounded by gadgets we take for granted while our distant neighbors in the Global South often go without even running water. We waste tons of food and spend billions on advertising, mostly aimed to convince us to purchase yet more unnecessary products that we’ll probably end up throwing away.

So it’s ironic that we feel Katniss’ loathing for the Capitol, laugh and cringe at how pathetic its citizens are. Because they are we.

Effie Trinket’s preoccupation with manners and decorum shields her from the savagery of the Games. She is any of us who deny our own participation in injustice around the world while we buy clothes made in sweat shops or coffee unfairly traded. Those of us who are literally paralyzed by the scope of the injustice. Those of us who can’t imagine how to effect change, so we distract ourselves from our inability to get involved, to help in any way.

Effie Trinket’s preoccupation with manners and decorum shields her from the savagery of the Games. She is any of us who deny our own participation in injustice around the world while we buy clothes made in sweat shops or coffee unfairly traded. Those of us who are literally paralyzed by the scope of the injustice. Those of us who can’t imagine how to effect change, so we distract ourselves from our inability to get involved, to help in any way.

Game-maker Seneca Crane sees only the terrible beauty of the Games he creates. He seems almost unaware of their brutality or their value as propaganda for the Capitol. He and the rest of the Capitol’s citizens who mindlessly support the Games are a too-honest reflection of those of us who participate in our own military-industrial complex. Or the sensationalism of our news-media. Or the unsustainable pace of our instant-gratification culture. We let the spectacle of it all distract us from the brutal consequences of our lifestyle.

Game-maker Seneca Crane sees only the terrible beauty of the Games he creates. He seems almost unaware of their brutality or their value as propaganda for the Capitol. He and the rest of the Capitol’s citizens who mindlessly support the Games are a too-honest reflection of those of us who participate in our own military-industrial complex. Or the sensationalism of our news-media. Or the unsustainable pace of our instant-gratification culture. We let the spectacle of it all distract us from the brutal consequences of our lifestyle.

We tell ourselves The Hunger Games is just a movie. Because that makes it safe, so we don’t have to take seriously what we saw in its mirror.

But we’d do well to listen to The Hunger Games‘ warning. To see how we are the Capitol. Because until we admit that shameful truth about ourselves, we can’t begin to take the necessary steps to change.