I understand why the hippo did it. — Max

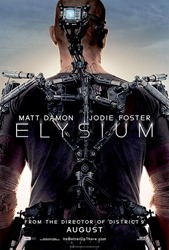

Elysium is the last of the 2013 summer blockbusters, and this year saved the best for last. Forget Star Trek Into Darkness or Man of Steel or even Pacific Rim (though it’s a close second). With his second film Elysium, director Neil Blomkamp (of District 9 fame) gives us a tightly-plotted, well-acted and thrillingly-executed dystopian thriller that leaves us with plenty to chew on. It’s also one of the only films this summer that’s not a sequel or reboot (Pacific Rim, The Heat and The Conjuring are among the few others, and they’re all spectacular).

Elysium is the last of the 2013 summer blockbusters, and this year saved the best for last. Forget Star Trek Into Darkness or Man of Steel or even Pacific Rim (though it’s a close second). With his second film Elysium, director Neil Blomkamp (of District 9 fame) gives us a tightly-plotted, well-acted and thrillingly-executed dystopian thriller that leaves us with plenty to chew on. It’s also one of the only films this summer that’s not a sequel or reboot (Pacific Rim, The Heat and The Conjuring are among the few others, and they’re all spectacular).

Blomkamp’s District 9 was a not-so-subtle reflection on apartheid (Blomkamp’s a native South African), and even the trailer for Elysium reveals this film confronts immigration just as directly. Though many complain Elysium is too heavy-handed, I disagree. My favorite sci-fi is always social commentary with a thin layer of glossy tech (::cough:: Star Trek). And given the state of our American conversation on Immigration – and the continued actions of the states of Arizona and Texas, we could clearly handle a bit less subtlety when it comes to immigrants.

But as the film’s title implies, Blomkamp isn’t just talking about immigration. Elysium wants to say something about religion, too.

Elysium is a space station where Earth’s wealthiest elite live. Elysium takes its name from the Elysium Fields, the ancient Greek equivalent of Heaven, reserved for the children of gods and heroes of legend. And indeed, Elysium is Heaven. No war, no crime, no poverty. No illness and no death. On Elysium, humanity has finally achieved the dream we had in Genesis 11: we built a tower to the sky and became gods.

Elysium is a latter-day Tower of Babel, an image of human hubris.

That ought to make the film’s parallels to contemporary America all the more disturbing. From our (American) first world perspective, a space station for Earth’s elite seems farcical. But anyone who’s ever visited the two-thirds world knows that’s exactly how many of the global poor view our country. We’re a land of impossible luxury and wealth, as distant, unobtainable and impenetrable as a futuristic space station.

Even more, Elysium‘s picture of religion out to disturb we religious people who live in the first world. If Elysium is a manufacture Heaven, the droid-infrastructure becomes a stand-in for religion. In the film, droids manage everything, from policing and private security to parole monitoring. The droids are responsible to keep the citizens of Elysium safe, ignorant and happy. They keep the rest of humanity out of sight and out of mind.

Religion often functions the same way: our churches are structured to cater to the insiders, to the ‘religious’ folk, to the people who are already going ‘up there’. Our preaching, our hospitality (or lack thereof), our language and our liturgies all conspire to keep bad people out and good people in (good being like us and bad being different, of course).

We too often use religion as a barrier between God and those we deem unworthy.

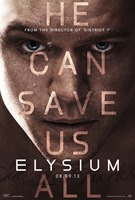

Evangelicalism does it today, as did the Pharisees of Jesus’ time. And this is the real brilliance of Blomkamp’s film: Max is a Christ-figure who tears down heaven so everyone can reach “god”. Whereas Jesus left heaven and became human, Max becomes less-than-human, by donning the exoskeleton, so he can enter heaven. Whereas Jesus willingly surrendered his life for humanity, Max is at first selfish: he only wants to be healed himself.

Ultimately, Max becomes a Jesus-figure when he chooses to die wholly for the good of those he loves. There’s nothing in it for him, no advantage, no possibility of rescue. He finds himself not in reaching the beauty of Heaven Elysium, but in embracing Earth Frey.

Max finally learns what counts as beautiful religion, a lesson a nun taught him as a child: as beautiful as we think Heaven looks, true beauty is found here, among God’s creations.

It’s worth noting Max isn’t a 1-to-1 Jesus-figure. Since there’s no explicit God figure, we also don’t get any incarnation story. Max isn’t a lost child of Elysium raised in the slums of Los Angeles or anything. He’s just an ordinary guy who dreams of Heaven Elysium. There’s also no resurrection: Max simply dies to open heaven up to the rest of us. But the story works great, and after the heavy-handed Jesus-imagery in Man of Steel, Max’s subtler messiah is a breath of fresh air.

Elysium warns how easily religion can become a tool of Empire.

Empires always set themselves up as gods. Empires can only enjoy extravagant wealth by denying the humanity of everyone else. The violence of Death is always the final enemy, and the final weapon of Empire. These are true in Elysium because they’re always true. They’re human truths.

And as Max demonstrates, only death can shatter the Empire’s false heaven, unblock religion and affirm the full humanity of every person. Once Max has sacrificed himself, Elysium’s religious droid infrastructure finally begins to serve all humanity, not just the wealthy 1%. Heaven comes down to Earth and all humanity is finally rescued. Pretty cool way to end a story!