Dawn of the Planet of the Apes might just be the movie of the summer. It certainly beat out other early contenders like X-Men: Days of Future Past and Edge of Tomorrow to be the most profound and poignant of the blockbusters (Guardians of the Galaxy is the movie to beat this summer, since you didn’t ask).

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes might just be the movie of the summer. It certainly beat out other early contenders like X-Men: Days of Future Past and Edge of Tomorrow to be the most profound and poignant of the blockbusters (Guardians of the Galaxy is the movie to beat this summer, since you didn’t ask).

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes is way better than any movie that’s a sequel to a reboot of a reboot of a 5-film franchise that peaked in the first film.

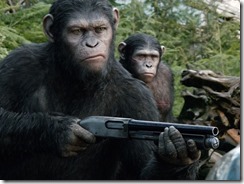

Much of Dawn’s success should be credited to Andy Serkis, who reprises his role as the lead ape, Caesar. The special effects in this film are on a level we haven’t seen before – it’s nearly impossible to tell what’s real and what’s CG. And the actors who play the apes imbue them with a level of humanity that demands our sympathy. It really is magical.

Dawn picks up 10 years after its predecessor (the good-but-not-great reboot Rise of the Planet of the Apes). Humanity has been devastated by the misnamed Simian Flu that escaped from the lab in the last film – less than 10 million people are left alive on the whole planet. Caesar and his apes, meanwhile, have established the beginnings of an ape civilization.

The first 15 minutes or so of the film follow Caesar and his people. We see them communicating in sign language, see them hunting together, witness a sort of medical caste and a proto-educational system. The apes communicate with symbol, with language. The world-building, the ape culture, is so good in this film, it’s hard to undersell. The apes have not merely mimicked human culture, but truly created their own unique society. Dawn realizes this ape world so wholly and masterfully it seems effortless. It’s pure filmmaking genius.

The first 15 minutes or so of the film follow Caesar and his people. We see them communicating in sign language, see them hunting together, witness a sort of medical caste and a proto-educational system. The apes communicate with symbol, with language. The world-building, the ape culture, is so good in this film, it’s hard to undersell. The apes have not merely mimicked human culture, but truly created their own unique society. Dawn realizes this ape world so wholly and masterfully it seems effortless. It’s pure filmmaking genius.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes uses apes and humans to tell a powerful story about the dangers of tribalism.

In the apes’ first confrontation with the humans (led by the level-headed Malcolm), Caesar towers powerfully over them and shouts, “GO!” It’s a tense, frightening moment, the first interaction between humans and apes in at least two years. We see how the humans perceived the encounter a few scenes later, when Malcolm’s son Alexander draws the confrontation. In Alexander’s imagination, Caesar is a terrifying Lovecraftian creature, his most monstrous features exaggerated beyond recognition.

Alexander’s drawing is emblematic of how the humans see the apes: they’re monsters crawling out of our collective nightmares, the new gods of the world in the wake of humanity’s fall. They’re harbingers of extinction, they’re bringers of disease, they’re enemies to be destroyed. They’re anything but people.

The extent to which Dawn humanizes the apes is a testament to the film’s power and brilliance.

Humans aren’t the only ones who hate. Caesar believes the best in humans, due largely to his upbringing with Will Rodman (James Franco in Rise). It’s no accident that the symbol of Caesar’s house is a recreation of Rodman’s attic window. Koba, Caesar’s right-hand ape, on the other hand, knew only cruelty from humanity. As Caesar remarks to his son, Blue Eyes,

Humans aren’t the only ones who hate. Caesar believes the best in humans, due largely to his upbringing with Will Rodman (James Franco in Rise). It’s no accident that the symbol of Caesar’s house is a recreation of Rodman’s attic window. Koba, Caesar’s right-hand ape, on the other hand, knew only cruelty from humanity. As Caesar remarks to his son, Blue Eyes,

Koba learned cruelty from the humans… but little else.

Koba’s past marked him as surely as Caesar’s marked him. One of the most tense (and awesome) moments in the film is when Koba confronts Caesar about his decision to aid the humans at the dam – when he spits the words “Human. Work.” again and again while pointing at his various scars.

Koba and Caesar represent two possible ape responses to the human race (and, therefore, two possible human responses to the Other): Koba represents fear, mistrust and tribalism, the scarcity worldview where We can’t thrive as long as They exist.

Caesar represents the possibility of peace, the willingness to see past the Tribe, to work to forgive and seek understanding even when you’ve been wronged.

Koba’s path of tribalism brings death, while Caesar’s commitment to peacemaking brings life.

Koba not only tries to assassinate Caesar, his coup leads the apes to unnecessary war against the humans. As Koba consolidates his power, he breaks the apes’ code, including “Ape not kill Ape” – when he kills Ash for not obeying him – and “Apes together strong” – when he imprisons those apes too loyal to Caesar. In the end, Koba’s choices result in his death, as he is reduced to fighting not only Caesar, but all his ape allies.

Caesar, on the other hand, is able to recover from his wounds and defeat Koba. Each time Koba defies him, he talks Koba back into submission, with Koba kneeling and stretching up his arm in a plea for forgiveness and a promise of allegiance. Each time, Caesar accepts. Their final fateful encounter sees Caesar beating Koba into submission, which leads Koba to his betrayal. In the film’s final action sequence, Caesar stands over Koba, his hand gripping Koba’s, keeping him from falling to his death, mirroring the posture of reconciliation. Koba wickedly throws Caesar’s first rule back in his face – “Ape not kill ape”, to which Caesar replies “You are no ape,” before dropping Koba to his death.

Caesar’s point is clear: by his actions, Koba has dehumanized (deapified?) himself to the point he’s not part of the community, and therefore not subject to their rules anymore.

Ultimately, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes takes a pessimistic view of humanity’s capacity for overcoming violence and making peace:

Apes started war. But humans will not forgive. – Caesar

I thought we had a chance. – Malcolm

So did I. – Caesar

In the end, despite Caesar and Malcolm’s best efforts, war has begun in earnest between humans and apes. The surviving humans have called in some sort of military response, and the apes have no recourse but to stand and fight. (Incidentally, if we’re fortunate enough to get a sequel, it will probably be something akin to Battle for the Planet of the Apes. We can only hope we’re so lucky.)

In the end, despite Caesar and Malcolm’s best efforts, war has begun in earnest between humans and apes. The surviving humans have called in some sort of military response, and the apes have no recourse but to stand and fight. (Incidentally, if we’re fortunate enough to get a sequel, it will probably be something akin to Battle for the Planet of the Apes. We can only hope we’re so lucky.)

Despite a world that’s more than big enough (especially in the wake of the Simian Flu) for both apes and humans, their tendency toward tribalism has torn them apart. They cannot coexist, cannot see past their differences to their shared humanity.

Is there any hope?

At Dawn’s third act is winding up, Alexander once again draws Caesar, this time fully realized, powerful and beautiful. The differences between the two pictures couldn’t be more stark. In the first, Caesar is a monster, a boogeyman, a terror. In the second, he’s no less powerful, no less capable, but now Alexander truly sees him. Not just as a warrior or king, but as a father, a husband, a friend. Through their interactions, Alexander has developed empathy for Caesar, and this lets him see Caesar as he truly is, not as he first appeared.

At Dawn’s third act is winding up, Alexander once again draws Caesar, this time fully realized, powerful and beautiful. The differences between the two pictures couldn’t be more stark. In the first, Caesar is a monster, a boogeyman, a terror. In the second, he’s no less powerful, no less capable, but now Alexander truly sees him. Not just as a warrior or king, but as a father, a husband, a friend. Through their interactions, Alexander has developed empathy for Caesar, and this lets him see Caesar as he truly is, not as he first appeared.

Similarly, Caesar’s son, Blue Eyes, was blinded by Koba’s hatred and prejudice. But as he saw the fruit of Koba’s actions, he began to see Koba’s way was toxic. After he chooses to release Malcolm, he’s reunited with his father, and when Caesar is able to show him the truth (that Koba shot him), Blue Eyes too is able to see the humans (and Koba) for what they truly are.

Similarly, Caesar’s son, Blue Eyes, was blinded by Koba’s hatred and prejudice. But as he saw the fruit of Koba’s actions, he began to see Koba’s way was toxic. After he chooses to release Malcolm, he’s reunited with his father, and when Caesar is able to show him the truth (that Koba shot him), Blue Eyes too is able to see the humans (and Koba) for what they truly are.

In the end, they all realize that the world isn’t divided into Humans and Apes. Into Us and Them. It’s divided into people who hate and people who love. People who choose to believe the best and those who choose to believe the worst. Alexander and Blue Eyes choose the path of love, the path of trust. Will that win the day? Who can say? We’ll have to wait for the sequel.