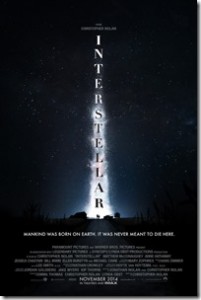

INTERSTELLAR is the new Christopher Nolan film starring Matthew McConaughey. The film is beautiful, majestic, powerful – in short, it’s everything we expect from a Nolan film. It’s also a bit hollow, which hints at some interesting developments in Nolan’s filmmaking trajectory.

INTERSTELLAR is the new Christopher Nolan film starring Matthew McConaughey. The film is beautiful, majestic, powerful – in short, it’s everything we expect from a Nolan film. It’s also a bit hollow, which hints at some interesting developments in Nolan’s filmmaking trajectory.

INTERSTELLAR marks Nolan’s most optimistic film to date. It’s not a perfect film, but it’s moving in the right direction, indicating that Nolan’s best work may be ahead of him.

The film is set in the near future – about a generation or so from the present. The Earth is in bad shape – wheat and okra are a distant memory, lost to blight, governments can’t sustain militaries anymore, technological progress has nearly ceased. Most humans still alive (in America, at least – we intentionally don’t get a view of the rest of the world), and they see themselves as a “Caretaker Generation”.

The Earth has been used up by humanity, with particular blame levied at 20th Century American excess, and the powers that be blame innovation and progress – there’s a funny, sharp scene near the beginning that takes aim at history text book intentionally revising history.

Pitted against all of this is Cooper (McConaughey), who was once a test pilot but now farms. He is recruited by the allegedly-defunct NASA (operating now in secret and conveniently close to Cooper’s Mid-West farm!) to pilot a follow-up mission to the far reaches of outer space. The goal? To find more habitable planets. Cooper chooses to leave his two kids, and how he navigates the tension between trying to save the human race and be reunited with his family drives the film’s plot.

As scripts go, INTERSTELLAR is serviceable. But the visual storytelling make the film a must-see.

As scripts go, INTERSTELLAR is serviceable. But the visual storytelling make the film a must-see.

Nolan has gone on record repeatedly as a huge fan of IMAX format, and each of his films includes more and more IMAX footage. INTERSTELLAR proves why Nolan loves the format: if you can see INTERSTELLAR on a huge IMAX screen, do yourself a favor and go. (If you weren’t aware there’s a difference between 70mm IMAX and 35mm “lieMAX”, check this out.) This film was made to be seen as big as possible, and you’ll thank yourself for making the extra effort to find a 70mm screen.

The effects are good, but anyone who’s seen GRAVITY, the Oscar-winning Alfonso Cuaron film from last year, will be a bit disappointed. These two films were obviously in development at the same time (both took years to make it to the big screen), but Curaon proved more innovative in terms of representing space and weightlessness (Nolan does a work-around with artificial gravity). INTERSTELLAR, on the other hand, is a bigger film in terms of scope and science – the way the film plays with time, in particular, is creative and gut-wrenching.

And we can’t forget to give credit to Hans Zimmer’s outstanding score – always one of the best characters in any Nolan film!

But excellent visuals, powerful score and creative storytelling are what we’ve come to expect fro Nolan. What’s really interesting about INTERSTELLAR is its thematic troubles.

Spoilers for INTERSTELLAR after the jump

INTERSTELLAR is basically a post-Apocalyptic film. It begins with the same sort of pessimism concerning the future we find any zombie film or young adult trilogy out right now. Or any of the dozens of other films we’ve seen out in recent memory. But from the beginning, INTERSTELLAR evinces a fundamental optimism about humanity’s future.

When Cooper is told he and his son are part of the Caretaker Generations, he fumes that humans aren’t caretakers. “We’re explorers and inventers.” Unlike most post-apocalyptic or dystopian films, Cooper isn’t raging against a corrupt institution or twisted pseudo-government. He’s raging against entropy (more or less – that’s actually problematic, but we’ll get to that.). Cooper is convinced humankind should be able to overcome the dying of the Earth.

INTERSTELLAR embodies the Myth of Progress. It’s a huge step forward for Nolan, but it also demonstrates he has a ways to go.

Nolan’s early films are shockingly pessimistic. I think we all love Memento, but try to find a film that has a bleaker picture of human nature. His Batman films are the first to have something we could comfortably identify as a hero, and it takes three films for him to achieve a legitimate victory (only made possible by “abandoning his one rule”). Nolan’s view of human nature and human potential to this point has been decidedly negative, and INTERSTELLAR marks a clear shift in that view. We could rightly have expected Nolan to deliver us a post-apocalyptic film more like The Road, that ends in bleak pessimism, querying whether hope is actually a wise decision at all.

Nolan’s early films are shockingly pessimistic. I think we all love Memento, but try to find a film that has a bleaker picture of human nature. His Batman films are the first to have something we could comfortably identify as a hero, and it takes three films for him to achieve a legitimate victory (only made possible by “abandoning his one rule”). Nolan’s view of human nature and human potential to this point has been decidedly negative, and INTERSTELLAR marks a clear shift in that view. We could rightly have expected Nolan to deliver us a post-apocalyptic film more like The Road, that ends in bleak pessimism, querying whether hope is actually a wise decision at all.

But that’s not at all what we get. If Michael Cain’s incessant quoting of Dylan Thomas’ “Do not go gentle into that good night” doesn’t put enough cheese on your nachos, at one point in INTERSTELLAR, Cooper affirms to Professor Brand (Cain),

“We’ll find a way, Professor. We always do.”

This is the Myth of Progress in a nutshell: the conviction that humans are enough in and of ourselves, that no matter what comes our way, we will – through ingenuity and hard work – prevail. That as a race we are advancing, so whatever obstacles we face, we will overcome them.

The film bears this out: the first act is filled with mysteries. What is this “ghost” that haunts Murph’s room? Who put this wormhole by Saturn so that we can reach habitable worlds? How can we see inside a black hole so we can crack the mystery of gravity?

The film bears this out: the first act is filled with mysteries. What is this “ghost” that haunts Murph’s room? Who put this wormhole by Saturn so that we can reach habitable worlds? How can we see inside a black hole so we can crack the mystery of gravity?

The answer to all these questions is We did it! It turns out gravity cuts across space-time, and future humans have evolved into 5th-dimensional beings. Future-us reach back to give us the tools we need to escape Earth. (Why they don’t go back further and tell us to stop screwing up Earth in the first place is not explained.)

In INTERSTELLAR, Nolan seeks to mitigate contemporary Western pessimism about the future, essentially saying, “Yes, things are getting worse, but we’ll find a way. We always do.”

Murph most purely illustrates the film’s essential optimism: she complains to her father that he named her after something bad – Murphy’s Law. In popular culture, Murphy’s Law is quoted as “Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong.” But according to Cooper (and some probably-apocryphal internet research), Murphy’s Law is more properly stated as “Anything that can happen, will happen.”

The problem with INTERSTELLAR’s optimism is that it’s largely groundless and unexamined.

Nolan tells us a story in which progress will save us, but from what do we need saving? According to the film, we need to be save from, uh… Human progress. We have to leave the Earth because we’ve used it up. Human progress did that. And if that tension were explored, the film would be much more profound and interesting. But it’s not. Nolan apparently doesn’t see any contradiction in the role of Progress in the film. And that in itself may point to a deeper problem.

INTERSTELLAR is from start to finish a masculine film. Despite two great performances from Jessica Chastain and Anne Hathaway (and Mackenzie Foy as young Murph!), INTERSTELLAR feels heartless and rational. Cooper’s wife died before the film opens, depriving us of any maternal perspective in the film. And Cooper rejects the younger Brand’s plea to follow her heart – a decision that proves to be wrong. (Brand is played by Hathaway and her mother is also deceased. Are there no moms left in this future Earth?)

With the female perspective so underrepresented and casually discarded, is it a coincidence that Mother Earth is so thoughtlessly abandoned, so little mourned?

No, INTERSTELLAR’s attitude toward Earth – that it is nothing more than a resource to use up and then abandon with no more thought than we would give to a used candy wrapper is a decidedly industrialist mentality, one that arises directly from the Myth of Progress and that has been demonstrated to be masculine. If the film were more self-aware, I would point out that Cooper abandons his children for his job as a critique of modern masculinity, but I don’t think Nolan meant it as a critique. For him, that seems just to be what men do.

On the small scale, too, INTERSTELLAR struggles to get the human element right. Nolan has never done love well, from Leonard and Natalie’s dysfunctional relationship in Memento to Sarah and Alfred Borden’s mercurial marriage in The Prestige to Bruce Wayne’s never-quite-consummated loves with Rachel and Selina in the Dark Knight trilogy.

So that all the human relationships in INTERSTELLAR seem to be filmed at arm’s length wasn’t particularly surprising. But Cooper’s drive to return to his children (particularly Murph) is the first time we’ve seen a Nolan character driven by love for a living person (rather than for vengeance or ambition). Cooper doesn’t have to learn to love (as did Bruce Wayne), and Murph is alive and well and waiting for him.

The human relationships are a weakness for INTERSTELLAR, but a big jump forward for Nolan.

This is INTERSTELLAR: a big shift in the perspective of one of the most important directors working right now. Time will tell, but it seems as though Nolan is becoming more optimistic as he gets older.

The film’s biggest problem thematically is its blind embrace of the Myth of Progress. In this regard, it’s a latter-day retelling of the Tower of Babel, though not on purpose. Because progress is uncritically elevated to a salvific role, the film misses an opportunity to explore the role of progress in human destiny in a more fully nuanced way. Progress becomes a deity that offers more than it can possibly deliver, especially when we take seriously the fate of the Earth and (apparently) the billions of humans who die as a direct result of the fruits of progress. It should be at least a little bit troubling that progress only apparently saves rich, white Americans.

Again, if the film were more self-reflective, this could be an incisive critique of the Myth of Progress. But Nolan seems either oblivious to or unbothered by these aspects of his film.

6 replies on “INTERSTELLAR and the Myth of Progress”

Love the review JR and I’ll have a lot more to say later, but right off there is the huge plot hole about future “us’s” as 5th dimensional beings. If “they” didn’t help Cooper, then humans wouldn’t have survived at all to become “they.” So how were “they” able to exist in order to allow Cooper to use gravity to communicate across time? Furthermore, as you pointed out, why wouldn’t “they” have intervened earlier in our “evolution/devolution?” Even more fundamental than that, the conversation between Cooper and TARS in the holo-deck reveals that “they” are unable to communicate directly with humans so Cooper must. Um, just because I learn a new language, does that mean I forget the old one? Also, they were able to create a field in which Cooper’s consciousness could function so if they could conceive of that, why did they need a cooper to do the manual work? And you’re right, the AI robots in this are the best characters. All humans are flat or head-strong. Why would the AI be the only source of humor? Do I give Nolan credit for making a point here? … That’s probably the biggest challenge I have. Where do I give Nolan credit and where is he just super blind or dismissive? That’s what I’ll chat about later… Much love!

When talking about the problem Nolan has with love and emotion, i think the best point made about the film is how TARS shouldn’t be our favorite character… good call.

I had an issue with Murph’s character as an adult. After watching all the messages from his son, we get one finally in there from his daughter. So she hasn’t disappeared but has shown up because of an important birthday. Okay, awesome. That whole scene had been powerful, and I was locked in. But then we pan back and she’s working for NASA with Professor Brand. HUH? So she dedicated her whole life to the Lazarus program and worked with the professor (a father figure to be sure) who sent her dad off, but she STILL never understood why he left? If anyone would understand why he had to go it should be one of the key researchers in the program. Maybe she’s just a really hurt kid all grown up, but I went from lump in my throat to wth in a hurry.