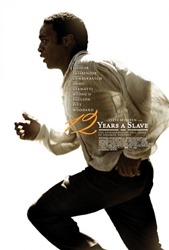

By now you’ve no doubt heard the buzz about Steve McQueen’s bloody, brutal new film 12 Years a Slave. Set in the Antebellum South, 12 Years tells the story of Solomon Northrop, a free Northern black man who’s kidnapped and sold into slavery.

By now you’ve no doubt heard the buzz about Steve McQueen’s bloody, brutal new film 12 Years a Slave. Set in the Antebellum South, 12 Years tells the story of Solomon Northrop, a free Northern black man who’s kidnapped and sold into slavery.

Right off the bat, let me add to the accolades: 12 Years a Slave is beautiful. It’s well-acted. It’s the sort of film that, as the credits roll, feels important.

I felt awful at the film’s close – which very much seems to be the film’s purpose. (That’s not necessarily a criticism – plenty of amazing films don’t leave me feeling happy afterwards. Gone Baby Gone and Arlington Road leap immediately to mind). Of course, 12 Years a Slave played on my white guilt. Not only am I a person of relative privilege – I grew up in a suburban home with two parents who both have post-graduate degrees, etc. etc., but at least one of my direct ancestors was a Virginia plantation owner.

I’m not alone in my discomfort: several black reviewers have noted the film provoked a similar response in them – shame and degradation.

The question, then: is the shame and guilt 12 Years a Slave fosters in its viewers a good thing? I say No, it’s not.

Not because depictions of violence are always in-and-of themselves bad. When violence is depicted on screen, we should ask: why? What purpose does the violence serve? What effect does it have on the story? What affect does it have on us, the audience? (We can and should ask the same of other aspects of the film, including sexuality and langauge.)

Not because depictions of violence are always in-and-of themselves bad. When violence is depicted on screen, we should ask: why? What purpose does the violence serve? What effect does it have on the story? What affect does it have on us, the audience? (We can and should ask the same of other aspects of the film, including sexuality and langauge.)

The question, then is Does the violence and dehumanization pay off? I didn’t find the final scene redemptive. Sweet? Yes. Relieving? Absolutely. But did a fumbling, inappropriate apology and an awkward embrace rehumanize Solomon Northrop after 2 hours of unrelenting brutality? Not in my book. (If it worked for you, the rest of this won’t make a lot of sense.)

So: because the ending lacked sufficient redemption, 12 Years a Slave creates shame, guilt and degradation in its viewers, but doesn’t do anything with them. We’re meant to feel these feelings for the sake of feeling them. That’s about it. And that’s a big problem.

Shame for shame’s sake isn’t redemptive. It’s condemnation.

Contrarian movie critic Armond White – whose distaste for the film is already infamous – compared 12 Years a Slave to another brutal, bloody film that likewise feels weighty and important in the moment: The Passion of the Christ. Though Armond mentions the comparison passingly in his review, the two films’ similarities in goal and tone deserve more attention.

Contrarian movie critic Armond White – whose distaste for the film is already infamous – compared 12 Years a Slave to another brutal, bloody film that likewise feels weighty and important in the moment: The Passion of the Christ. Though Armond mentions the comparison passingly in his review, the two films’ similarities in goal and tone deserve more attention.

Both 12 Years and Passion of the Christ are artistic, beautiful period pieces. But the periods in question are shameful, sinful moments in history: the former our great national shame and the latter the day humanity killed God. Both films invite us to participate in the events by watching. And the viewing experience offers us a kind of salvation from the guilt tied to those events.

Because that salvation based in witnessing the violence itself rather than in triumph over that violence, neither film offers any actual hope for either the victims or the victimizers.

Both 12 Years a Slave and The Passion of the Christ are built on a particular understanding of atonement – of how sin once committed can be made right. The particular theological model is called Penal Substitution, a fancy term that essentially means someone else is punished as a substitute for the sinner.

Both 12 Years a Slave and The Passion of the Christ are built on a particular understanding of atonement – of how sin once committed can be made right. The particular theological model is called Penal Substitution, a fancy term that essentially means someone else is punished as a substitute for the sinner.

In the case of The Passion of the Christ, Jesus is suffering on behalf of all humanity. In the case of 12 Years a Slave, it’s a bit trickier: we as the viewers are invited to sympathize with Solomon; he’s the clear protagonist. As we watch him (and his fellow slaves) suffer, we suffer with him. The effect – for me and for everyone I’ve talked to who’s seen the film – was exactly the same as their viewing of Passion of the Christ:

Because we know the story is true, we are compelled not to turn away. To watch. To face up to the brutal, bloody truth of the matter. By watching the suffering, the films become cathartic – they allow us to experience the horror of the events without actually having to engage the horror in real life.

They show us something objectively awful: in both cases, human beings dehumanized by torture. But it’s through a screen, at a distance. We can participate vicariously, without getting our hands dirty.

Penal Substitution works when we feel guilt and shame over what’s being wrought. The more guilt, the better.

This becomes a vicious cycle: the worse the acts depicted on the screen, the worse we feel in the moment and thus the better we feel later. Films that function the way 12 Years and Passion of the Christ work better the more violence they show. The worse the violence, the more guilt and shame they evoke. In that sense, guilt and shame are easy emotions – easy to depict, easy to manufacture. And powerful enough to be mistaken for helpful motivation.

This becomes a vicious cycle: the worse the acts depicted on the screen, the worse we feel in the moment and thus the better we feel later. Films that function the way 12 Years and Passion of the Christ work better the more violence they show. The worse the violence, the more guilt and shame they evoke. In that sense, guilt and shame are easy emotions – easy to depict, easy to manufacture. And powerful enough to be mistaken for helpful motivation.

Armond’s description of 12 Years a Slave as “torture porn” isn’t far off the mark. With it (and Passion of the Christ), we already know the story is bad. We just watch to see how bad it gets before the end. The violence titillates us. The suffering manipulates our emotions, summons guilt and shame and it all comes pouring out as the credits roll in great waves of tears and then we leave.

And it’s over. Because, after all, it was just a movie.

And that’s the real danger of these films. As Joe Morton points out in his excellent HuffPo piece on 12 Years, what we need is not one more depiction of slavery to make us all feel sad. If we’re truly going to conquer race issues, we need to see black heroes and pioneers. Stories of black persons whose hero’s journeys aren’t any different from something we’d see from Liam Neeson, Matt Damon or Angelina Jolie.

And that’s the real danger of these films. As Joe Morton points out in his excellent HuffPo piece on 12 Years, what we need is not one more depiction of slavery to make us all feel sad. If we’re truly going to conquer race issues, we need to see black heroes and pioneers. Stories of black persons whose hero’s journeys aren’t any different from something we’d see from Liam Neeson, Matt Damon or Angelina Jolie.

In other words, what we need to make films like 12 Years a Slave work is resurrection. Good triumphing over evil. And not as an epilogue, an afterthought like we got in 12 Years (and Passion of the Christ).

But as long as we have films that let us release some pent up guilt, that let us feel like something important happened when all we did was watch a movie, we’ll never move forward. We need stories about redemption, not just about suffering. Suffering by itself doesn’t save. We need resurrection.